Abstract

Nosocomial infections or healthcare associated infections occur in patients under medical care. These infections occur worldwide both in developed and developing countries. Nosocomial infections accounts for 7% in developed and 10% in developing countries. As these infections occur during hospital stay, they cause prolonged stay, disability, and economic burden. Frequently prevalent infections include central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, surgical site infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Nosocomial pathogens include bacteria, viruses and fungal parasites. According to WHO estimates, approximately 15% of all hospitalized patients suffer from these infections. During hospitalization, patient is exposed to pathogens through different sources environment, healthcare staff, and other infected patients. Transmission of these infections should be restricted for prevention. Hospital waste serves as potential source of pathogens and about 20%–25% of hospital waste is termed as hazardous. Nosocomial infections can be controlled by practicing infection control programs, keep check on antimicrobial use and its resistance, adopting antibiotic control policy. Efficient surveillance system can play its part at national and international level. Efforts are required by all stakeholders to prevent and control nosocomial infections.

Keywords

1. Introduction

‘Nosocomial’ or ‘healthcare associated infections’ (HCAI) appear in a patient under medical care in the hospital or other health care facility which was absent at the time of admission. These infections can occur during healthcare delivery for other diseases and even after the discharge of the patients. Additionally, they comprise occupational infections among the medical staff [1]. Invasive devices such as catheters and ventilators employed in modern health care are associated to these infections [2].

Of every hundred hospitalized patients, seven in developed and ten in developing countries can acquire one of the healthcare associated infections [3]. Populations at stake are patients in Intensive Care Units (ICUs), burn units, undergoing organ transplant and neonates. According to Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC II) study, the proportion of infected patients within the ICU are often as high as 51% [4]. Based on extensive studies in USA and Europe shows that HCAI incidence density ranged from 13.0 to 20.3 episodes per thousand patient-days [5].

With increasing infections, there is an increase in prolonged hospital stay, long term disability, increased antimicrobial resistance, increase in socio-economic disturbance, and increased mortality rate. Spare information exists on burden of nosocomial infections because of poorly developed surveillance systems and inexistent control methods. For instance, while getting care for other diseases many patients probably get respiratory infections and it becomes troublesome to spot the prevalence of any nosocomial infection in continuation of a primary care facility [5]. These infections get noticed only when they become epidemic, yet there is no institution or a country that may claim to have resolved this endemic problem [6].

We have discussed the control strategies of nosocomial infections in our previous study [7]. In this review article a brief description about the distribution of these infections across the globe, emerging causes, brief control methods but more focus on current surveillance will be discussed.

2. Types of nosocomial infections

The most frequent types of infections include central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, surgical site infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia. A brief detail of these is given below:

2.1. Central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI)

CLABSIs are deadly nosocomial infections with the death incidence rate of 12%–25% [8]. Catheters are placed in central line to provide fluid and medicines but prolonged use can cause serious bloodstream infections resulting in compromised health and increase in care cost [9]. Although there is a decrease of 46% in CLABSI from 2008 to 2013 in US hospitals yet an estimated 30,100 CLABSI still occur in ICU and acute facilities wards in US each year [10].

2.2. Catheter associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI)

CAUTI is the most usual type of nosocomial infection globally [11]. According to acute care hospital stats in 2011, UTIs account for more than 12% of reported infections [12]. CAUTIs are caused by endogenous native microflora of the patients. Catheters placed inside serves as a conduit for entry of bacteria whereas the imperfect drainage from catheter retains some volume of urine in the bladder providing stability to bacterial residence [11]. CAUTI can develop to complications such as, orchitis, epididymitis and prostatitis in males, and pyelonephritis, cystitis and meningitis in all patients [12].

2.3. Surgical site infections (SSI)

SSIs are nosocomial infections be fall in 2%–5% of patients subjected to surgery. These are the second most common type of nosocomial infections mainly caused by Staphylococcus aureus resulting in prolonged hospitalization and risk of death [13]. The pathogens causing SSI arise from endogenous microflora of the patient. The incidence may be as high as 20% depending upon procedure and surveillance criteria used [14].

2.4. Ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP)

VAP is nosocomial pneumonia found in 9–27% of patients on mechanically assisted ventilator. It usually occurs within 48 h after tracheal incubation [15]. 86% of nosocomial pneumonia is associated with ventilation [16]. Fever, leucopenia, and bronchial sounds are common symptoms of VAP [17].

3. Nosocomial pathogens

Pathogens responsible for nosocomial infections are bacteria, viruses and fungal parasites. These microorganisms vary depending upon different patient populations, medical facilities and even difference in the environment in which the care is given.

3.1. Bacteria

Bacteria are the most common pathogens responsible for nosocomial infections. Some belong to natural flora of the patient and cause infection only when the immune system of the patient becomes prone to infections. Acinetobacter is the genre of pathogenic bacteria responsible for infections occurring in ICUs. It is embedded in soil and water and accounts for 80% of reported infections [18]. Bacteroides fragilis is a commensal bacteria found in intestinal tract and colon. It causes infections when combined with other bacteria [19]. Clostridium difficile cause inflammation of colon leading to antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis, mainly due to elimination of beneficial bacteria with that of pathogenic. C. difficile is transmitted from an infected patient to others through healthcare staff via improper cleansed hands [19]. Enterobacteriaceae (carbapenem-resistance) cause infections if travel to other body parts from gut; where it is usually found. Enterobacteriaceae constitute Klebsiella species and Escherichia coli. Their high resistance towards carbapenem causes the defense against them more difficult [20]. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) transmit through direct contact, open wounds and contaminated hands. It causes sepsis, pneumonia and SSI by travelling from organs or bloodstream. It is highly resistant towards antibiotics called beta-lactams [20].

3.2. Viruses

Besides bacteria, viruses are also an important cause of nosocomial infection. Usual monitoring revealed that 5% of all the nosocomial infections are because of viruses [21]. They can be transmitted through hand-mouth, respiratory route and fecal-oral route [22]. Hepatitis is the chronic disease caused by viruses. Healthcare delivery can transmit hepatitis viruses to both patients and workers. Hepatitis B and C are commonly transmitted through unsafe injection practices [20]. Other viruses include influenza, HIV, rotavirus, and herpes-simplex virus [22].

3.3. Fungal parasites

Fungal parasites act as opportunistic pathogens causing nosocomial infections in immune-compromised individuals. Aspergillus spp. can cause infections through environmental contamination. Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans are also responsible for infection during hospital stay [22]. Candida infections arise from patient’s endogenous microflora while Aspergillus infections are caused by inhalationof fungal spores from contaminated air during construction or renovation of health care facility [23].

4. Epidemiology of nosocomial infections

Nosocomial infection affects huge number of patients globally, elevating mortality rate and financial losses significantly. According to estimate reported of WHO, approximately 15% of all hospitalized patients suffer from these infections [23]. These infections are responsible for 4%–56% of all death causes in neonates, with incidence rate of 75% in South-East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The incidence is high enough in high income countries i.e. between 3.5% and 12% whereas it varies between 5.7% and 19.1% in middle and low income countries. The frequency of overall infections in low income countries is three times higher than in high income countries whereas this incidence is 3–20 times higher in neonates [24].

5. Determinants

Risk factors determining nosocomial infections depends upon the environment in which care is delivered, the susceptibility and condition of the patient, and the lack of awareness of such prevailing infections among staff and health care providers.

5.1. Environment

Poor hygienic conditions and inadequate waste disposal from health care settings.

5.2. Susceptibility

Immunosupression in the patients, prolonged stay in intensive care unit, and prolonged use of antibiotics.

5.3. Unawareness

Improper use of injection techniques, poor knowledge of basic infection control measures, inappropriate use of invasive devices (catheters) and lack of control policies [25]. In low income countries these risk factors are associated with poverty, lack of financial support, understaffed health care settings and inadequate supply of equipments [5].

6. Reservoirs and transmission

6.1. Microflora of patient

Bacteria belonging to the endogenous flora of the patient can cause infections if they are transferred to tissue wound or surgical site. Gram negative bacteria in the digestive tract cause SSI after abdominal surgery.

6.2. Patient and staff

Transmission of pathogens during the treatment through direct contacts with the patients (hands, saliva, other body fluids etc.) and by the staff through direct contact or other environmental sources (water, food, other body fluids).

6.3. Environment

Pathogens living in the healthcare environment i.e. water, food, and equipments can be a source of transmission. Transmission to other patient makes one more reservoir for uninfected patient [22].

7. Prevention of nosocomial infection

Being a significant cause of illness and death, nosocomial infections need to be prevented from the base line so that their spread can be controlled.

7.1. Transmission from environment

Unhygienic environment serves as the best source for the pathogenic organism to prevail. Air, water and food can get contaminated and transmitted to the patients under healthcare delivery. There must be policies to ensure the cleaning and use of cleaning agents on walls, floor, windows, beds, baths, toilets and other medical devices. Proper ventilated and fresh filtered air can eliminate airborne bacterial contamination. Regular check of filters and ventilation systems of general wards, operating theatres and ICUs must be maintained and documented. Infections attributed to water are due to failure of healthcare institutions to meet the standard criteria. Microbiological monitoring methods should be used for water analysis. Infected patients must be given separate baths. Improper food handling may cause food borne infections. The area should be cleaned and the quality of food should meet standard criteria [22].

7.2. Transmission from staff

Infections can be transferred from healthcare staff. It is the duty of healthcare professionals to take role in infection control. Personal hygiene is necessary for everyone so staff should maintain it. Hand decontamination is required with proper hand disinfectants after being in contact with infected patients. Safe injection practices and sterilized equipments should be used. Use of masks, gloves, head covers or a proper uniform is essential for healthcare delivery [22].

7.3. Hospital waste management

Waste from hospitals can act as a potential reservoir for pathogens that needs proper handling. 10–25% of the waste generated by healthcare facility is termed as hazardous. Infectious healthcare waste should be stored in the area with restricted approach. Waste containing high content of heavy metals and waste from surgeries, infected individuals, contaminated with blood and sputum and that of diagnostic laboratories must be disposed off separately. Healthcare staff and cleaners should be informed about hazards of the waste and it’s proper management [22].

8. Control of nosocomial infections

Despite of significant efforts made to prevent nosocomial infections, there is more work required to control these infections. In a day, one out of 25 hospital patients can acquire at least a single type of nosocomial infection [26].

8.1. Infection control programs

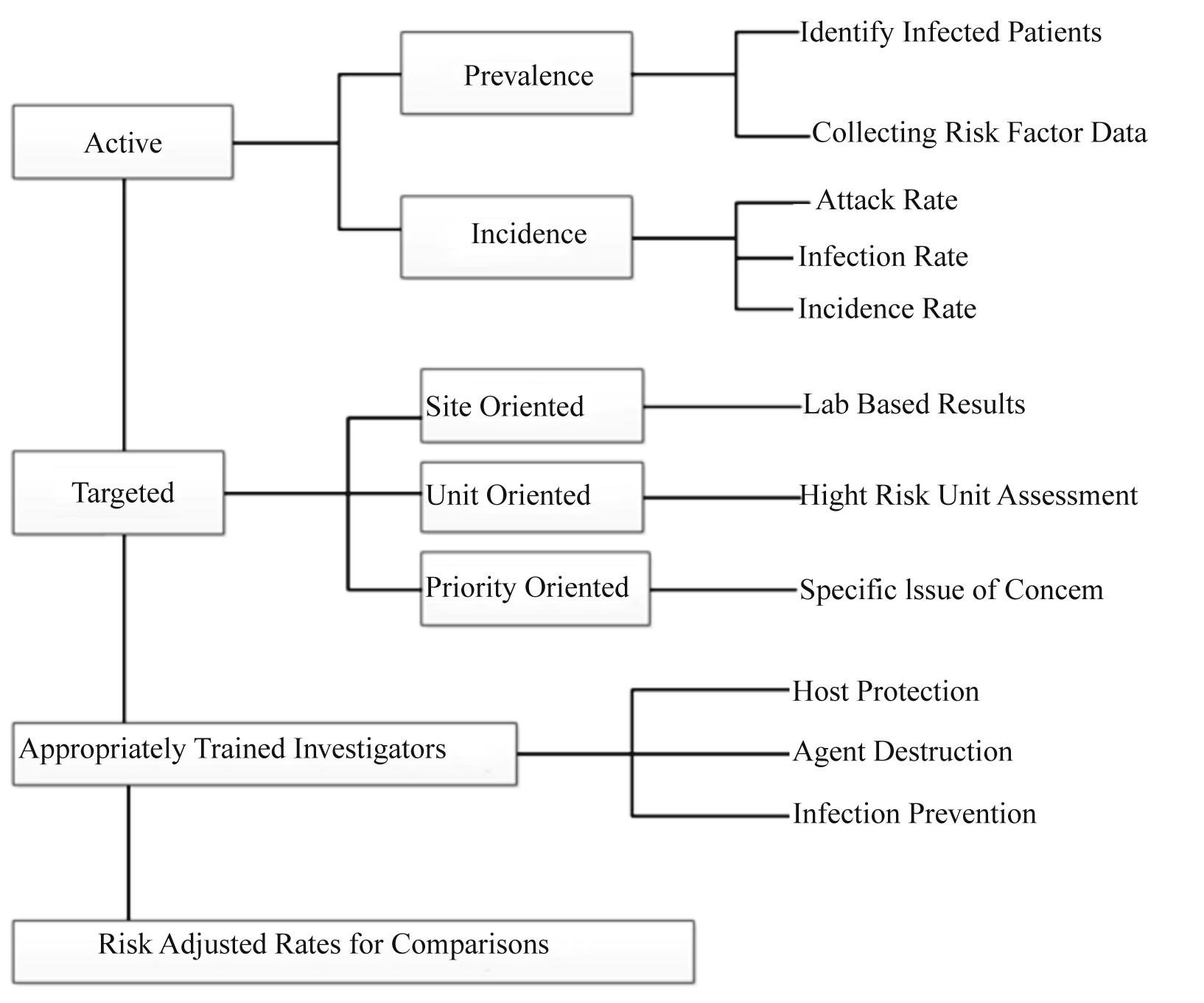

Figure 1. Infection control program.

9. Antimicrobial use and resistance

Microbes are the organisms too small to be seen with the eyes, yet they are found everywhere on earth. Antimicrobial drugs are used against the microbes which are pathogenic towards living organisms. Antimicrobial resistance occurs when the microbes develop the ability to resist the effects of drugs; they are not killed and their growth does not stop.

9.1. Appropriate antimicrobial use

Antibiotics are greatly used to cure illness. Antimicrobial use should justify the proper clinical diagnosis or an infection causing microorganism. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that each year about 100 million courses of antibiotics are prescribed by office-based physicians, while approximately 50% of those are unnecessary [27]. The selection of antimicrobials should be based upon the patient’s tolerance in addition to the nature of disease and pathogen. The aim of antimicrobial therapy is to use a drug that is selectively active against most likely pathogen and least likely to cause resistance and adverse effects [22]. Antimicrobial prophylaxis should be used when it is appropriate i.e. prior to surgery, to reduce postoperative incidence of surgical site infections. In case of immunocompromised patients, prolonged prophylaxis is used until immune markers are reinstate [28].

9.2. Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance is responsible for the death of a child every five minutes in South-East Asia region. Drugs that were used to treat deadly diseases are now losing their impact due to emerging drug resistant microorganisms [29]. Self medication with antibiotics, incorrect dosage, prolonged use, lack of standards for healthcare workers and misuse in animal husbandry are the main factors responsible for increase in resistance. This resistance threatens the effective control against bacteriathat causes UTI, pneumonia and bloodstream infections. Highly resistant bacteria such as MRSA or multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are the cause of high incidence rates of nosocomial infections worldwide [30]. South-East Asian region reports reveal that there a high resistance in E. coli and K. pneumoniae for third generation cephalosporin and more than quarter of S. aureus infections are methicillin resistant [31]. “Immediate action is needed to stop the world from heading towards pre-antibiotic era in which all achievements made in prevention and control of communicable diseases will be reversed”, said Dr Poonam Khetrapal Singh, Regional Director of WHO South-East Asia Region [32].

9.3. Antibiotic control policy

The worldwide pandemic of antibiotic resistance shows that it is driven by overuse and misuse of antibiotics, which is a threat to prevent and cure the diseases. WHO’s global report on antibiotic resistance, preventing the infection from happening by better hygiene, clean water, and vaccination to reduce the need of antibiotics. The development of new diagnostics and other tools is required in healthcare institutes to stay ahead of evolving resistance. Pharmacists should play their role of prescribing the right antibiotic when truly needed and policymakers should foster cooperation and information among all stakeholders [31].

10. Surveillance of nosocomial infection

Although the aim of infection prevention and control program is to eradicate nosocomial infections but epidemiological surveillance for demonstration of performance improvement is still required to accomplish the aim. The efficient surveillance methods include data collection from multiple sources of information by trained data collectors; information should include administrative data, demographic risk factors, patients‘ history, diagnostic tests, and validation of data. Following the data extraction, analysis of the collected information should be done which includes description of determinants, distribution of infections, and comparison of incidence rates. Feedback and reports after analysis should be disseminated by infection control committees, management, and laboratories keeping the confidentiality of individuals. The evaluation of credibility of surveillance systems is required for effective implementations of interventions and its continuity. Finally the undertaking of data at regular intervals for maintenance of efficiency of surveillance systems should be made compulsory [22]. Efficient methodology for appropriate surveillance approach is given in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Organization for efficient surveillance [21].

11. Conclusion

With increased burden of nosocomial infections and antimicrobial resistance, it has become difficult for healthcare administrations and infection control committees to reach the goal for elimination of intervals. However, by practicing sound and healthy ways for care delivery designed by infection control committees, controlling transmission of these infections using appropriate methods for antimicrobial use, the resistance in emerging pathogens against antimicrobials can be reduced easily. An efficient surveillance method guided by WHO can help healthcare institutes to devise infection control programs. Proper training of hospital staff for biosafety, proper waste management and healthcare reforms and making general public aware of these endemic infections can also help in reduction of nosocomial infections.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1]

-

WHOThe burden of health care-associated infection worldwide(2016)[Online] Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/burden_hcai/en/[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [2]

-

CDCTypes of healthcare-associated infections. Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs)(2016)[Online] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/HAI/infectionTypes.html [Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [3]

-

G.M. Raja Danasekaran, K. AnnaduraiPrevention of healthcare-associated infections: protecting patients, saving livesInt J Community Med Public Health, 1 (1) (2014), pp. 67-68

- [4]

-

J.L. Vincent, J. Marshall, E. Silva, A. Anzueto, C.D. Martin, R. Moreno, et al.International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care unitsJAMA, 302 (21) (2009), pp. 2323-2329

- [5]

-

B. AllegranziReport on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwideWHO, Geneva (2011)

- [6]

-

A. Gupta, D.K. Singh, B. Krutarth, N. Maria, R. SrinivasPrevalence of health care associated infections in a tertiary care hospital in Dakshina Kannada, Karnataka: a hospital based cross sectional studyInt J Med Res Health Sci, 4 (2) (2015), pp. 317-321

- [7]

-

H. Khan, A. Ahmad, R. MehboobNosocomial infections and their control strategiesAsian Pac J Trop Biomed, 5 (7) (2015), pp. 509-514

- [8]

-

Vital signs: Central line–associated blood stream infections – United States, 2001, 2008, and 2009Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 60 (08) (2011), pp. 243-248

- [9]

-

WHOPreventing bloodstream infections from central line venous cathetersWHO, Geneva (2016)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [10]

-

CDCBloodstream infection event (central line-associated bloodstream infection and non-central line-associated bloodstream infection)CDC, Atlanta, Georgia (2015)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [11]

-

J.W. WarrenCatheter-associated urinary tract infectionsInt J Antimicrob Agents, 17 (4) (2001), pp. 299-303

- [12]

-

CDCUrinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection [CAUTI] and non-catheter associated urinary tract infection [UTI]) and other urinary system infection [USI]) eventsCDC, Atlanta, Georgia (2016)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [13]

-

D.J. AndersonSurgical site infectionsInfect Dis Clin North Am, 25 (1) (2011), pp. 135-153

- [14]

-

C.D. OwensSurgical site infections: epidemiology, microbiology and preventionJ Hosp Infect, 70 (Suppl 2) (2008), pp. 3-10

- [15]

-

J.D. HunterVentilator associated pneumoniaBMJ, 344 (2012), pp. 40-44

- [16]

-

M. Steven, J.D.T. KoenigVentilator-associated pneumonia: diagnosis, treatment, and preventionClin Microbiol Rev, 19 (4) (2006), pp. 637-657

- [17]

-

D.E.C. HjalmarsonVentilator-associated tracheobronchitis and pneumonia: thinking outside the boxClin Infect Dis, 51 (Suppl 1) (2010), pp. S59-S66

- [18]

-

G. Suresh, G.M.L. JoshiAcinetobacter baumannii: an emerging pathogenic threat to public healthWorld J Clin Infect Dis, 3 (3) (2013), pp. 25-36

- [19]

-

A. JayanthiMost common healthcare-associated infections: 25 bacteria, viruses causing HAIs, Becker’s hospital review(2014)

- [20]

-

CDCDiseases and organisms in healthcare settings. Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs)CDC, Atlanta, Georgia (2016)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [21]

-

C.J.D. AitkenNosocomial spread of viral diseaseClin Microbiol Rev, 14 (3) (2001), pp. 528-546

- [22]

-

J.F. Ducel, L. NicollePrevention of hospital-acquired infectionsWHO, Geneva (2002)

- [23]

-

R.M. Emily, T.M.P. SydnorHospital epidemiology and infection control in acute-care settingsClin Microbiol Rev, 24 (1) (2011), pp. 141-173

- [24]

-

S.B. Nejad, S.B. Syed, B. Ellis, D. PittetHealth-care-associated infection in Africa: a systematic reviewBull World Health Org, 89 (2011), pp. 757-765

- [25]

-

N.K. Chand WattalHospital infection prevention: principles & practicesSpringer, New York (2014)

- [26]

-

CDCHAI data and statistics. Healthcare-associated infectionsCDC, Atlanta, Georgia (2016)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [27]

-

R. ColganAppropriate antimicrobial prescribing: approaches that limit antibiotic resistanceAm Fam Physician, 64 (6) (2001), pp. 999-1005

- [28]

-

S. Leekha, R.S. EdsonGeneral principles of antimicrobial therapyMayo Clin Proc, 86 (2) (2011), pp. 156-167

- [29]

-

P.K. SinghAntibiotics, handle with careWHO, Geneva (2016)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [30]

-

WHOAntimicrobial resistanceWHO, Geneva (2014)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

- [31]

-

WHOWHO’s first global report on antibiotic resistance reveals serious, worldwide threat to public healthWHO, Geneva (2014)

- [32]

-

WHOUrgent action needed to prevent a return to pre-antibiotic era: WHOWHO, Geneva (2015)[Online] Available from:[Accessed on 10th August, 2016]

-

Peer review under responsibility of Hainan Medical University. The journal implements double-blind peer review practiced by specially invited international editorial board members.